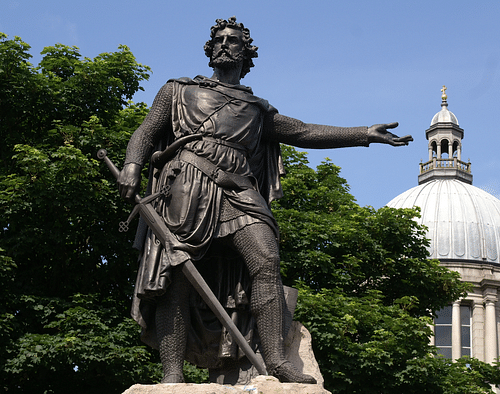

Sir (c. 1270-1305) was a Scottish knight and national hero who fought for his country's independence from England. Wallace famously led the Scots to victory against a larger English army at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in September 1297.

The English king Edward I of England (r. 1272-1307) was intent on revenge and conquering Scotland, but his victory at Falkirk against Wallace in 1298 could not ultimately subdue the Scots. Wallace was captured in Glasgow and tried for treason in London in 1305. Inevitably found guilty, Wallace was given the worst possible sentence: to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. William Wallace then became a martyr, the ultimate heroic patriot, and the subject of countless legends, ballads, and poems. He did not live to see it but Scotland did indeed gain independence under the rule of Robert the Bruce (r. 1306-1329).

AdvertisementWilliam Wallace was born c. 1270 into a landowning family in southwest Scotland. His father was a knight, minor noble, and vassal of James Stewart, the 5th High Steward of Scotland. Tradition has it that Wallace was born in Elderslie near Paisley in Renfrewshire or Elderslie in Ayrshire. Wallace was traditionally portrayed as a commoner in later medieval sources or even as a thief or outlaw in posthumous biographies, but this is likely because Scottish writers wished to portray him as a 'man of the people' and English ones as an ignoble enemy. Technically, Wallace was an outlaw in English eyes because his family did not sign their name to the 'Ragman Rolls', a list compiled in the summer of 1296 of all the Scottish tenants who promised allegiance to the English Crown. William Wallace, as far as we know, never married and had no children.

William Wallace’s first attack of note was on Lanark in Scotland in May 1297 when the English sheriff was killed.

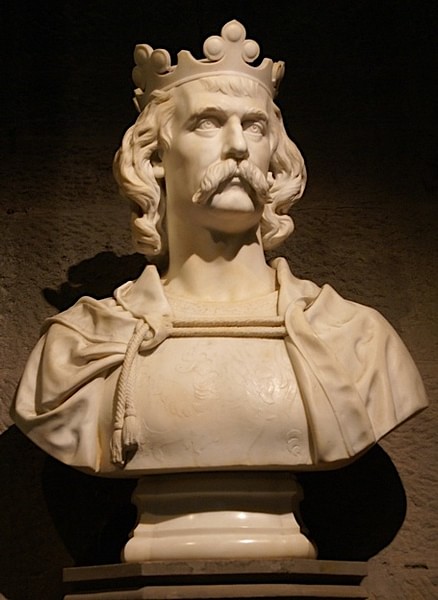

Edward I of England, known for his fiery temper and self-confidence, was nicknamed 'Longshanks' because of his height: 1.9 metres (6 ft 2 in), an unusually impressive stature for the period. The English king was already a battle-hardened campaigner. He had participated in the Ninth Crusade (1271-1272 CE), helped defeat the rebel English barons who had plotted against his father, and fought with distinction in Wales. Now Edward turned his sights on Scotland. A prelude to the military action was Edward’s decision in 1287 to begin expelling all Jews from his kingdom and to confiscate their property - a significant boost to his war chest. Then, towards the end of 1290, a golden opportunity presented itself to the English king: a succession crisis in Scotland.

Advertisement

Edward was invited to adjudicate on who would be the successor to Alexander III of Scotland (r. 1249-1286). Alexander had died without children and so the next best choice was his granddaughter Margaret, aka the 'Maid of Norway’ (b. 1283). Tragically, Margaret died during her voyage to Scotland in September 1290. The royal house of Canmore was at an end, and the Scottish nobles jostled for the throne. Unable to reach a decision, Edward was asked to select the best candidate, but in November 1292 the English king simply chose someone who could act as his puppet ruler in Scotland: John Balliol (r. 1292-1296). Balliol’s rule turned out to be so weak and ineffective that nobles began to gather around the Bruce family as an alternative, then led by Robert Bruce (b. 1210 CE), grandfather of his more famous namesake.

The ballad The Acts & Deeds of Sir William Wallace, Knight of Elderslie was the inspiration for the 1995 film Braveheart.

Rebellion was in the air, not only concerning the incompetent John but also because of Edward’s imposition of heavy taxes on the Scots to pay for his campaigns in France where Gascony was under serious threat. Then, in 1295, there came a major blow to Edward’s ambitions when Scotland formally allied itself with France - the first move in what became known as the 'Auld Alliance' - and Balliol felt confident enough to renounce his fealty to Edward. The rival Bruce family did not support the rebellion or Balliol’s rejection of fealty to the English king.

AdvertisementTo regain his grip on Scotland, Edward led an army in person to Berwick in March 1296 where, according to the 14th-century chronicler Walter of Guisborough, he massacred 11,060 of the town’s residents. Edward enjoyed the support of the Bruces, and at the Battle of Dunbar in April 1296, Balliol was defeated; the Scottish king surrendered, was stripped of his crown, and then kept captive in the Tower of London. Three English barons were selected to rule Scotland, and Edward even stole the Stone of Scone (aka Stone of Destiny) which was a symbol of the Scottish monarchy, relocating it to Westminster Abbey. In effect, the Scottish monarchy was at an end, at least in the eyes of Edward. It was in this chaotic climate of war, rebellion, and an empty throne that William Wallace makes his first appearance.

Wallace’s first raid of note was on Lanark in Scotland in May 1297 which he attacked with a band of some 30 men. In later legend, this raid was in revenge for an attack on Wallace’s sweetheart Marion and the murder of a group of Scottish nobles by English soldiers. William Heselrig, the English sheriff at Lanark was killed in the attack. More successful raids followed on Scone and several English garrisons between the rivers Forth and Tay before Wallace and his men retreated to the safety of the Highlands.

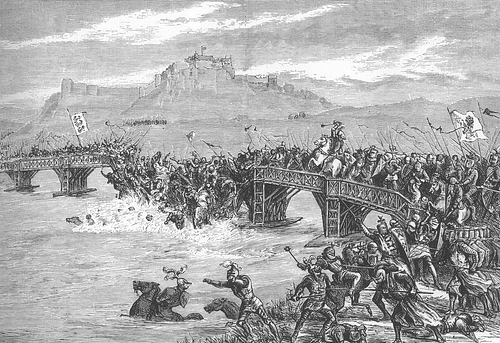

William Wallace's greatest triumph was his rout of an English army at the Battle of Stirling Bridge near Stirling Castle in central Scotland on 11 September 1297. The English army, which included at least 300 heavy cavalry, was led by John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, and was much larger than the Scottish force. The Scots were led by Wallace and Sir Andrew Moray of Bothwell (aka Andrew Murray) who had been leading a separate rebellion in the north of Scotland. In the usual preliminary negotiation before battle, legend has it that William boldly declared to the English representatives:

AdvertisementGo back and tell your people that we have not come for the benefit of peace, but are ready to fight, to avenge ourselves and to free our kingdom.

(Jones, 345).

Using the confines of a narrow bridge crossing the Forth River, which partially blocked the enemy army’s progress, Wallace attacked the isolated English vanguard when it reached the other side of the river. Forced back to the bridge, this structure collapsed under the weight of men and many drowned in the river weighed down by their armour. Alternative accounts of the battle have the Scots deliberately destroying the bridge or the English doing so to prevent the Scots pursuing them back across the river. Whatever the details, the outcome was clear: a resounding Scottish victory. Over 100 English knights were killed in the battle, including Sir Hugh de Cressingham, Edward's treasurer in Scotland, who had been hacked to pieces on Stirling bridge. Legend has it that Cressingham’s skin was used to make sporrans and sword belts to be worn by the victors.

Wallace then led raids into northern England, attacking Northumberland and Cumberland and launching sieges of Alnwick and Carlisle castles. He was so confident of control of his kingdom that in 1297 he and Moray wrote letters to traders in Lübeck and Hamburg that it was safe to resume international trade with Scotland. In March 1298 Wallace was knighted, most likely by Robert the Bruce, Earl of Carrick and the future Scottish king. In addition, Wallace was made “Guardian” of the Scottish government and commander-in-chief of its armies. These honours are good evidence that Wallace was no commoner but a man with excellent connections within the established Scottish nobility.

In 1298 Edward I led an army in person across the border. Wallace had been steadily retreating further north, avoiding a direct confrontation and employing a scorched earth policy to draw Edward’s army deeper into Scotland where his lack of supplies would become a serious logistics problem. The two armies finally met at the Battle of Falkirk on 22 July 1298. Edward’s army had large contingents of the much-feared longbow archers and English cavalry, and these routed the Scottish spearmen who had been arranged in front of Callendar Wood in their familiar battle order of four schiltroms (like hedgehogs but with bristling long spears instead of short spines). Edward had attacked the enemy on two sides and caused the small Scottish cavalry force to retreat in panic. Archers and crossbowmen then broke up the schiltroms with accurate and deadly fire. Around 20,000 Scots were killed, compared to 2,000 on the English side. Significantly, most of the Scottish nobles survived to fight another day. Wallace also escaped the victors but the ignominy of the defeat obliged him to resign his role as Guardian of Scotland.

AdvertisementThe events of the next few years are poorly documented. With a vacant throne, a ruling council had been established consisting of Wallace, John Comyn, and then Bishop Lamberton. Robert the Bruce did not initially support this council. Part of the problem was the Bruces had long been rivals of the Comyns, who supported the Balliols. On the other hand, Bruce did not now fully support Edward either, and he seems to have bided his time to better see the outcome of what has become known as the First War of Independence. After Falkirk and Wallace’s resignation as Guardian, the ruling council was led by the Bruces and Comyns, who temporarily settled their differences.

Robert the Bruce was at various moments clearly fully on the Scottish side and was involved, for example, in the attack on English-held Ayr Castle. However, in 1302 Robert's marriage to Elizabeth, daughter of an ally of Edward I, coupled with the release of John Balliol from the Tower of London meant that Robert once again sided with the English lest Balliol's Scottish allies succeed in reinstating the ex-king. The Bruce had ambitions for the throne himself.

Edward had sent more armies to Scotland in 1300, 1301, and 1303, recovering Stirling Castle in the process and so the situation in Scotland and who would rule was as complex as ever. After the debacle of Falkirk, the Scottish nobles studiously avoided any direct confrontation with English armies. However, Edward the English war-king was reaching the end of his long and active life, and Scotland could afford to bide its time.

Wallace, meanwhile, disappeared from public view, and although he was a wanted man, he managed to evade capture until 1305. In some accounts, he spent this period as a guerrilla fighter based in the Highlands, while other sources have him escape to France in the ship of the pirate Richard Longoville. Wallace may have sought French financial and military support to continue the fight for independence. An even more unlikely tale is that the Scottish hero made it to Rome where he pleaded with the Pope for aid in his fight with the English.

Wallace was finally caught in Glasgow on 5 August 1305, thanks to traitorous friends according to some medieval chroniclers. The most wanted man in Scotland was dragged to London to be prosecuted as a traitor to the Crown in Westminster Hall. Wallace was said to have been made to wear a crown of oak leaves to signify his lowly status as an outlaw. Wallace was formally charged with promoting Scotland’s allegiance with England’s enemy France, accused of killing innocent men, women, and children, including clergy during his raids in northern England, and charged with having led armies against the English Crown.

The Scotsman rejected the charges against him and declared that he owed loyalty only to his own king, the deposed John Balliol. Predictably found guilty of treason, on 23 August Wallace met the most gruesome death penalty an English court could dish out: to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. First, Wallace was stripped naked and dragged by his heels behind a horse through the streets of London. Reaching Smithfield, he was hanged but released from the noose just before death came. Laid out on a bench, his intestines were pulled from his body, he was then decapitated and his body chopped into four quarters. Wallaces’ head was put on public display on London Bridge as a warning to others, and the other four parts of his body were dispatched for public display in Aberdeen, Berwick, Newcastle, and Stirling, site of his great victory.

Love History?Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Robert the Bruce, meanwhile, was now having serious misgivings concerning his support for the English Crown. It seemed highly unlikely that Edward would ever make Robert king of Scotland. Steadily over the next year - and probably largely in secret - Robert began to work on gaining allies from key Scottish barons and eventually he was able to declare himself king in March 1306 (he would reign until 1329). Fortunately for Robert and the Scots, Edward I’s successor, his son Edward II of England (r. 1307-1327 CE), was militarily incompetent. After winning a great victory at Bannockburn in June 1314 CE, Robert was able to systematically remove the English invaders from Scotland one castle at a time.

William Wallace was gone but not forgotten, and his legend grew thanks to such epic and highly romanticised ballads as The Acts and Deeds of Sir William Wallace, Knight of Elderslie, written by either Henry the Minstrel or Blind Harry c. 1470. It is this colourful ballad which forms the basis of the 1995 film Braveheart. An important history of Wallace’s life, the History of William Wallace, was written in the 16th century. In the 1860s a Gothic monument was erected at Stirling to commemorate Wallace’s achievements. Still standing, the tower is an impressive 67 metres (220 ft) tall. Finally, fine statues of William Wallace and Robert the Bruce, who remain two of the greatest martial heroes in Scottish history, stand either side of the gatehouse of Edinburgh Castle, still today the symbolic heart of the kingdom they had fought so hard to keep free of foreign control.